Abd al-Nasser al-Qardash speaks

Abd al-Nasser al-Qardash in Iraqi custody. (source)

As the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria no longer controls territory, news of the group’s destruction of cultural heritage and trafficking in antiquities has faded from the headlines. The group is still active, and has been waging a rural insurgency in Iraq and Syria for the past year and half. Meanwhile, the loss of the physical caliphate has allowed historians a first chance to pick through its rubble.

Recently, Iraqi terrorism scholar Husham al-Hashimi was able to sit for a four-hour interview with Abd al-Nasser al-Qardash (real name: Taha Abd al-Raheem Abdallah Bakr al-Ghassani), the highest ranking leader of ISIS currently in Iraqi custody. Qardash made several statements about ISIS and antiquities trafficking which require closer examination.

al-Qardash was born in Mosul and grew up in Iraq’s Turkmen community. Inaccurate reports about his background have circulated for some time, including claims that he was a major general in the Iraqi Army under Saddam Hussein and that he served time in the infamous ISIS breeding ground of Camp Bucca in the early 2000s.[1] More recent information reveals he was in fact a civil engineer who was arrested in 2005 and imprisoned in Abu Ghraib.

At some point he joined Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s branch of al-Qaida in Iraq, which eventually morphed into the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. As ISIS seized territory in Iraq and Syria in 2014, he became the governor of Wilayat al-Barakah (otherwise known as Hasakah province in northeastern Syria) as well as a senior adviser to al-Baghdadi and a member of the Delegated Committee (who exercised authority on behalf of the caliph while al-Baghdadi was in deep hiding).

In May 2017 he became involved in a major power struggle which began over a debate about when it was appropriate to declare a Muslim to be takfir (an apostate from Islam). The details of this dispute have been explained elsewhere, but suffice to say that Qardash joined the hardline faction in this struggle. Several of his ideological opponents, most notably ISIS theologian Turki al-Bin’ali, met a sudden death by airstrike shortly after speaking out. al-Bin’ali’s supporters later accused his opponents within ISIS of leaking their locations to the international coalition as method of internal house-cleaning.

al-Qardash was dismissed from the Delegated Committee in September of that year. After al-Baghdadi was killed in October 2019, more inaccurate reports claimed al-Qardash was being considered as his successor. In fact, al-Qardash was already in custody, having been captured by the Syrian Democratic Forces in ISIS’ last stronghold of Baghouz in March 2019.

Iraqi government photo of al-Qardash in the custody of Iraq’s National Intelligence Service. (source)

The Syrian Kurds handed him over to the Iraqi government in May 2020. Since then he has been singing to whoever will listen, including multiple interviews and TV appearances. Much of what he has had to say for himself as been self-serving and self-exculpatory, such as claiming to have opposed ‘extremists’ within ISIS and to have no responsibility for the massacre of 700 members of the Shaytat tribe in Deir-ez-Zor or the decision to enslave the Yazidi population of Sinjar in 2014. Nevertheless, his experiences from 2017-2019 seem to have left him disillusioned with the organization, saying in his interview with al-Hashimi that “I pledged allegiance to al-Baghdadi and I am not obligated to pledge allegiance to [his successor] Abu Ibrahim al-Qurashi.”

With all appropriate caution, therefore, let us examine al-Qardash’s statements about antiquities trafficking and funding:

“We did not need to grow hashish, cocaine, or Indian hemp. We had an obscene abundance of antiquities. We tried to transfer the relics to Europe to sell them, but we failed in four major attempts. This is especially true for Syrian relics, which are well known and documented as a world heritage. So we resorted to destroying them and punishing those who trade in them.”

Drug trafficking has been a major source of revenue for terrorist organizations around the world for decades, but there has been little to no evidence that ISIS trafficked in narcotics as a major source of revenue. ISIS’ attempts to traffic in antiquities have been well documented in Deir-ez-Zor. However, despite frequent claims, proof that ISIS-smuggled antiquities have shown up in European or American auction houses has remained elusive. al-Qardash’s comments here may be illustrative as to why: artifacts from sites with distinctive material cultures like Palmyra or Mari are easily recognizable and their origins cannot be easily disguised.

The news that ISIS made ‘four major attempts’ to smuggle antiquities into Europe, each one failing, is intriguing, as it has generally been assumed that antiquities trade was carried out through middlemen in Turkey and Lebanon who bought Syrian antiquities for resale later. Did ISIS attempt to cut out the middlemen and sell directly to European dealers, thereby taking a greater percentage of the end price for themselves? This is not clear, but the possibility should be considered.

In any case, al-Qardash says these attempts were unsuccessful. More likely self-serving is his claim that ISIS punished artifact traffickers. While ISIS did publicly destroy artifacts seized from traffickers on several occasions, including several Palmyra funerary busts and a Neo-Assyrian stele from Tell Ajaja, these were destroyed because the traffickers were operated without permission from ISIS in order to avoid giving ISIS a cut of the proceeds. Further documentation has made it clear that ISIS banned excavation without a permit from the organization, which ensured that ISIS took a large share of any of the profits.

Regardless, al-Qardash provides a great deal of other information about ISIS’ internal funding which makes it clear that antiquities were not a major source of revenue for the organization. While claiming that Sami al-Jubouri,[2] who replaced Abu Sayyaf al-Tunisi as head of the Diwan al-Rikaz after the latter was killed in a US raid in May 2015, liked to keep the group’s finances secret, from what he know the main sources of funding in eastern Syria were:

- Oil smuggling, which he says netted the group $400 million. ISIS sold oil indiscriminately, even to the group’s enemies. According to al-Qardash oil smuggling was al-Jubouri’s primary concern rather than antiquities trafficking.

- Smuggling weapons and goods. It is not clear who ISIS may have been selling weapons to, rather than buying them.

- Ransom money from kidnappings. He specifically names local officials, journalists, and humanitarian workers as prime targets for securing a lucrative ransom. Reports of ransom money paid for hostages have usually been kept quiet, but the few reports which exist have discussed millions of dollars in ransoms.

- Selling bodies. Even more disturbingly, al-Qardash says the group made money from selling the bodies of persons killed in battle or executed by the group back to their families for burial.

- Looting. The seizure of property from opponents of the Islamic State has been well-documented elsewhere.

- Taxation. Like any government, ISIS attempted to extract revenue through taxes of various types, which al-Qardash says were levied on farmers and merchants.

Overall, al-Qardash says his budget as wali of Wilayah al-Barakah was $200 million in 2015, which funded all military forces in the province. This figure is roughly double the revenue reported from Wilayah al-Kheir (Deir-ez-Zor) at around the same time in an earlier post on this site. It is possible that Wilayah al-Barakah, on the frontlines of the battle against the Syrian Kurds, received a much higher budget than other provinces.

While al-Qardash’s interview is another piece of evidence that antiquities trafficking never made up a significant portion of ISIS’ revenue, it does reveal something about the Islamic State’s economy and why it proved unsustainable. Aside from oil, an inordinate amount of the Islamic State’s economy centered on taking assets away from its opponents and redistributing them to supporters of the Islamic State. According to al-Qardash:

Money is the biggest factor in encouraging young people to volunteer in the Iraqi-Syrian border areas. The poor social and economic conditions are a result of the tyranny of the ruling regimes, the absence of social justice, in addition to the involvement of most of the government leaders in corrupt practices, and their tendency to exclude shariah and Islamic culture from life, along with importing Western systems and values, without regard for cultural and societal sensitivities

ISIS had money, and used it to buy loyalty from many of the people who lived under their rule. The alternative was having your property confiscated and used to buy the loyalty of other people. But without an economy capable of creating new wealth there is a certain half-life as to how long this system can operate before it sputters to a halt.

References:

[1] Abdel Bari Atwan, Islamic State: The Digital Caliphate (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), 137-138.

[2] al-Jubouri is still at large, and is the subject of a $5 million reward from the US government for information leading to his death or capture.

Article © Christopher W. Jones 2020.

Reading Hazony by the Elgin Marbles

Yoram Hazony, The Virtue of Nationalism. New York: Basic Books, 2018. 285 pp.

Yoram Hazony, The Virtue of Nationalism. New York: Basic Books, 2018. 285 pp.

Liberal internationalism, we so often hear, is in retreat. Israeli political scientist Yoram Hazony’s new book caused a minor stir last fall by arguing that this might, if done properly, be a good thing.

Hazony’s vision for positive nationalism has more in common with Woodrow Wilson than Vladimir Putin, Viktor Orban, or Donald Trump: an international order consisting of independent sovereign states which derive their legitimacy from national self-determination and the maintenance of a monopoly on the legitimate use of force within their borders. They interact with each other via diplomacy, trade, and the exchange of ideas without intervening in each others’ internal affairs.

His argument depends on maintaining a dichotomy between Nationalism and Empire. Nationalism is particular, it is limited to a specific territory or people, and does not seek to impose itself on others. Empire, by contrast, has universal aspirations. Empire has a vision of a single moral order which it seeks to impose on the world.

Hazony traces the origins of the former category to ancient Israel, with the idea later coming into full flower in Protestant Europe after the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. In the latter category he lumps groups as diverse as the Roman Catholic church, Communism, the United States after World War II, the European Union, and Nazi Germany — grouped together only by their desire to impose a single moral vision on the rest of the world.

Plenty of other reviews have given these arguments substantial criticism: that setting forth guidelines for how states are to be organized is prescriptive and therefore imperialist, or that Hazony gives no reason why people can’t choose to band together to form international organizations just as they can choose to form nations. Furthermore, Hazony never addresses the blurred group boundaries which result from identity being a polyvalent, layered category.

I read Hazony’s book last fall, as I visited the British Museum every day to conduct research for my doctoral dissertation. Each day I walked by hundreds of amazing artifacts gathered from all over the world, acquired during the heyday of an Empire with universal aspirations. And so as I read Hazony by the Elgin Marbles, I want to focus on one aspect of his argument: his discussion of how the nation-state is constructed.

I read Hazony’s book last fall, as I visited the British Museum every day to conduct research for my doctoral dissertation. Each day I walked by hundreds of amazing artifacts gathered from all over the world, acquired during the heyday of an Empire with universal aspirations. And so as I read Hazony by the Elgin Marbles, I want to focus on one aspect of his argument: his discussion of how the nation-state is constructed.

A great weakness of most political theories of the state, from John Locke to Robert Nozick and John Rawls, is that their theories have no relation whatsoever to how states actually formed. Hazony attempts to address this by arguing that no state has ever been formed in the real world from a social contract based on the consent of the governed. In the real world, “mutual loyalties bind human beings into families, tribes, and nations, and each of us receives a certain religious and cultural inheritance as a consequence of being born into such collectives” (p. 31). Unless we live in a young country where we personally voted in favor of our nation’s current constitution, none of us have consented to the state we live in.

What does tie people together, according to Hazony, is blood: We feel great attachment to our parents and our siblings, even though we never consented to be related to any of them. A family begins with an act of consent (a marriage) but is tied together by family relations. Families grow and become clans, whose members are tied by bonds of shared ancestry even if they do not know each other. Heads of clans united to form tribes whose members number in the thousands. Heads of tribes can agree to unite to form a nation. (Families can also adopt new members, which is how Hazony seeks to head off accusations that his model is racist) (p. 66-70, 79-80, 87).

Hazony recognizes that there can be no such thing as a homogenous nation-state, but argues that having a dominant majority culture is the only way to ensure that citizens feel sufficient loyalty to each other to create social trust (p. 102-108, 137-138, 165-177). Minorities can be adopted into the state (the ideal model which Hazony has in mind for this is the ‘covenant of blood’ between the Druze minority and Jewish majority in his native Israel), but they must reconcile to being a minority in a state whose identity is defined by the dominant culture (p. 127-128).

Hazony argues that the so-called neutral state, which governs a territory without extending explicit favoritism to a particular culture or religion (such as the United States or France), is an illusion which only masks the cultural dominance of specific groups within that state. Documents such as the Declaration of Independence only serve as focal points for national unity because the WASPs who wrote them passed down a tradition to their children that these documents were to be revered, and they in turn passed down the same tradition to their own WASP children, in much the same way that a religious community venerates a sacred text (p. 156-166).

Hazony argues that the so-called neutral state, which governs a territory without extending explicit favoritism to a particular culture or religion (such as the United States or France), is an illusion which only masks the cultural dominance of specific groups within that state. Documents such as the Declaration of Independence only serve as focal points for national unity because the WASPs who wrote them passed down a tradition to their children that these documents were to be revered, and they in turn passed down the same tradition to their own WASP children, in much the same way that a religious community venerates a sacred text (p. 156-166).

Hazony’s views have some interesting implications for the debate over cultural property. Currently two primary models dominate the debate about “who owns the past?”:

1) Ownership rooted in the control of territory by the state. The state’s control of land (maintained through its monopoly on force) means it can pass laws governing that land, including laws declaring artifacts to be the property of the state to be managed for the benefit of all the state’s citizens. This is the current legal regime in much of the Mediterranean and the Middle East.

Yet many artifacts were exported prior to the creation of the modern states which control the territory where they were found, and those countries still ask for artifacts found in what is now their territory to be repatriated. In addition to the Elgin Marbles (exported from the Ottoman Empire in 1812, ten years before Greek independence) other recent high-profile restitution requests include Iraq asking for the return of an Assyrian relief sold at auction in New York (exported from the Ottoman Empire in 1859, 73 years before Iraq became a state) and Egypt’s repeated attempts to regain the Rosetta Stone (taken from French-occupied Mamluk Egypt in 1799, six years before Muhammad Ali Pasha established the modern Egyptian state and 36 years before Egypt’s first laws limiting the export of antiquities).

2) Ownership is rooted in identity and culture, with specific groups having a right to their own heritage as defined by cultural and blood ties. This model has achieved some legal recognition in the United States with the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) and in Israel, which has a longstanding policy of rescue acquisitions for Jewish artifacts.

Greece, Iraq, and Egypt are claiming a cultural right to artifacts exported before their countries were formed, rather than a legal right. Returning the Elgin Marbles might not be legally required, they say, but it is the moral thing to do, because they belong to Greeks.

However, the only type of state which can affirm this is one rooted in Hazony’s model. Greece can claim the Elgin Marbles as part of its cultural heritage because the modern state of Greece is 91.6% ethnic Greek, 99% of the population speaks the Greek language, 90% are members of the Greek Orthodox church, and they claim the Elgin Marbles as a physical manifestation of the shared traditions which give them a cultural identity. If Greece were a more diverse country, then such a claim could only be advanced by the portion of the population which considers themselves to be Greek. The Elgin Marbles would become the cultural heritage of part of the population who would have rights to it, but not of others – an arrangement granted legal recognition in the United States under NAGPRA but uncommon in the Mediterranean world.

Assyrian relief found at Nimrud in 1859 on the auction block at Christie’s in New York City on October 27, 2018. Photo by Amy Gansell.

But the opposite – arguing that all states have a right to everything found within their present-day borders – causes other difficulties. At panel discussion I attended at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in October of 2016 about threats to minority communities in the Middle East, one panelist stopped heritage discourse in its tracks by asking if it was acceptable for a state to kill or expel its minorities and then claim a right to their cultural heritage. This is not just an extreme hypothetical, as the long debate over the Iraqi Jewish Archive has made clear.

During the sale of the aforementioned Assyrian relief last October, the Assyrian American Association of Southern California produced a short video which was widely distributed on Facebook and Twitter, asking the anonymous buyer to consider what this ancient artifact means to the modern Assyrian people:

“Perhaps you can see now that this was never meant to be owned,” intones the video. “I hope that someday it finds its way home.” Where exactly “home” is, the video does not say. The majority of modern Assyrians have left Iraq and now form a diaspora scattered around the globe. The relief’s decontextualization from its place of discovery is held up as an emblem of the struggle of the Assyrian diaspora to maintain their identity.

While the Iraqi government attempted to file a claim because the relief was found in what is now Iraq, members of the Assyrian diaspora asserted a cultural right to the artifact based on its status as a symbol within their own cultural context.

And therein lies a problem which will increasingly become a challenge for cultural heritage in the 21st century: If a nation-state can claim a right to artifacts based on its dominant cultural identity, cultural identities without states can make the same claim. And since cultural identity is polyvalent and layered to the point where one person can usually claim several identities, deciding who should own what could begin a process resulting in either the reification of identity into easy to define groups, or a reduction of identity categories to the level of the individual.

The former entrenches division, the latter makes every individual a potential rightful owner of their own personal cultural heritage.

Article © Christopher Jones 2019.

Towards a Post-Westphalian Archaeology

The modern history of archaeological research can be roughly divided into three periods. During the first period, running from Napoleon’s 1798 expedition to Egypt to the end of World War 2, archaeology was often part of imperial enterprises. Archaeology was primarily (but not exclusively) conducted by Europeans and Americans who traveled to exotic lands in search of the remains of past civilizations. Disparities in wealth and power meant that a steady stream of artifacts flowed from poor regions to wealthy imperial capitals in London, Paris, Berlin and Istanbul. National museums conferred prestige by showcasing the breadth of their respective empires’ territory and influence.

Conceptually archaeology in the Near East was a search for ‘firsts’ – of agriculture, cities, the wheel, writing, laws, literature – that held the keys to understanding the genesis of civilization. Civilization then passed to the Greco-Roman world, and from there to the West. Westerners went east in search of their own origins, carrying with them a teleology which they subconsciously imposed on the shape of the field.[1]

The second period began in southern Europe in the nineteenth century, but spread in earnest only after World War 2 and ran until at least the early 2000s. In many places it continues to this day. As decolonization created new nation-states organized into a new international system by the United Nations, those states sought to take control of their own archaeology. Thanks to previous associations of archaeology with colonial control, establishing control of archaeological sites located within their territory became an important part of asserting their independence.[2]

The new period was a product of the new international system, in which the entire world and its population was divided into self-governing states which controlled defined geographic boundaries. Since the state’s realm of control is circumscribed by defined geographic boundaries, states could lay claim to all archaeological remains located within their borders, regardless of whether they had any direct or ongoing cultural link with the state’s present inhabitants. If it was found within the territory of the state, it was part of the heritage of that geographic locale, and was therefore part of the state.

States declared all artifacts found within their borders to be part of their national heritage. Artifacts found within their territory were declared state property and their export was banned. Archaeology was regulated by government ministries. Extensive diplomatic efforts sought the return of artifacts which had been removed from within the country’s modern borders during the previous period. National museums showcased all artifacts found within the state’s territory. Efforts were made to train native-born archaeologists to take over research in their home countries.

This had numerous positive results: it slowed the steady drain of artifacts from the developing to the developed world, promoted interest in the archaeology worldwide, and began to free the discipline from its colonialist past. Ideologically the recovery of the ancient past served as a form of resistance to cultural domination by the West, showing that these states had a civilized past which either pre-dated Western civilization or developed independently of it.

Yet the weakness of the second period was bound up in the weakness of the international system which created it. In the modern institution of the state belonging is marked by citizenship, which overrides social ties of family, language, ethnicity and religion. Both citizenship and geographic boundaries are on some level arbitrary: citizenship is granted by the state either at birth or by legal process, and borders are lines drawn on a map. All states are to some degree heterogeneous, containing many types of people lumped together into a common identity by the accident of borders.

Implied consent – the unavoidable difficulty that most people who are born into a state never participated in framing their constitution and therefore have never had a real say in forming the type of government they live under, and are therefore presumed to have consented to being governed by sole virtue of being born in a certain time and place – is an ever-present weakness in the system.

I will argue that we are now seeing the emergence of a third period of archaeology, which is being created by the erosion of the nation-state in the twenty-first century.

The state has weaknesses: Implied consent, heterogeneity and artificial borders all pose problems for maintaining the system. Some states have attempted to manage this through greater integration with other states. In some cases this has exacerbated the problem, driving people who no longer feel that they share a common life to fall back onto more primary loyalties even as global communications makes it easier than ever before for them to connect with like-minded people. As a result, ethnic nationalism is no longer necessarily linked to geographic boundaries but is defined solely by membership in the tribe.

Tribes have certain advantages over the state. Tribes select their own members and do not need to control a defined territory in order to exist, which means they do not face the problem of heterogeneous populations forced to share the same geographic space. Tribes are constantly changing as their members change, removing the problem of implied consent. They are prone to splitting, which conversely makes them adaptable.

As a result, twenty-first century national archaeology now seeks to supersede the apparatus of the state and use archaeology to promote the interests of the tribe.

Resurgent Russian Nationalism

Following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Vladimir Putin argued that Crimea was vital to Russian identity because “It was in Crimea, in the ancient city of Chersonesus or Korsun, as ancient Russian chroniclers called it, that Grand Prince Vladimir was baptised before bringing Christianity to Rus.” This was important because “Christianity was a powerful spiritual unifying force that helped involve various tribes and tribal unions of the vast Eastern Slavic world in the creation of a Russian nation and Russian state. It was thanks to this spiritual unity that our forefathers for the first time and forevermore saw themselves as a united nation.”

Of course, the archaeological site of Chersonesus lay outside the boundaries of the Russian state. But this did not matter, because in Putin’s view the essential qualities of Russian-ness are not citizenship in the Russian Federation but ties of culture, language and religion. In a 2015 interview with Charlie Rose, Putin lamented that after the break-up of the USSR “25 million of Russian people suddenly turned out to be outside the borders of the Russian Federation,” and in other statements has promised to use Russian power to protect the interests of ethnic Russians who are citizens of other states.

Putin’s critic and supporter from the right, Aleksandr Dugin, has articulated a post-Westphalian nationalist ideology in even starker terms:

I want to stress that, since the beginning of the fifteenth century, the state and the empire were seen as opposite extremes in Europe. Bodin, Machiavelli and Hobbes developed their theories of the ‘state’ in opposition to the ontology of the empire; the concept of the state is a product of the repudiation of the concept of an empire. The state is an artificial pragmatic construction, desacralised and devoid of telos, purpose and substance. On the contrary, the empire is something alive, sacred, and replete with purpose and essence: something that has a higher destiny. In an empire, the administrative apparatus is not separate from the religious mission, or from the people’s spirit. The empire is a universal embodiment of this mission, illuminating the elastic energy of people and culture.[3]

States are bound by geographic boundaries, empires expand. States treat all their citizens equally before the law, empires are free to privilege certain groups of people over others. But states are ultimately practical constructs, while empires are deeply ideological, and therefore can provide meaning to certain types of people in ways that states cannot. By extension, an empire can claim all archaeological sites which connect to its core identity regardless of geographic location.

Assyrian Nationalism

Not all forms of the new nationalism seek to rule over others. The Assyrian minority in Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Iran along with the Assyrian diaspora abroad strongly identify with the cultures of pre-Islamic Mesopotamia (or Beth Nahrain as it is known in modern Aramaic), especially the Assyrian Empire.

As Assyrian activist Mardean Isaac has put it:

If Christianity is all that is at stake, we can worship freely in the west. An Iraqi Christian can easily become a Kurdish Christian or a French Christian. Our living history and all that it comprises it is irreplaceable: our link to the past and the future of our people is our land and our language.

Of course, claiming that Nineveh and Nimrud are the special heritage of one ethnic minority directly undercuts the idea that Iraq’s ancient past is the heritage of all Iraqis. And yet at least half of Iraq’s Assyrian population has been forced to flee the country since 2003. At panel held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art this past September on protecting the cultural heritage of religious minorities in the Middle East, an Assyrian audience member directly questioned whether persons who aided and abetted genocide against an ethnic minority should be able to claim rights to that minority’s cultural heritage once that minority had been removed, simply because that heritage is located within the territory of a state of which they are a citizen.

While Assyrian nationalists have often called for the establishment of an Assyrian state, more realistic current goals seek the establishment of an autonomous region within Iraq in the region of Nineveh Plains similar to the status enjoyed by Iraqi Kurdistan.

Kurdish Nationalism

Oh, enemy! The Kurdish people live on,

They have not been crushed by the weapons of any time

Let no one say Kurds are dead, they are living

They live and never shall we lower our flagWe are the descendants of the Medes and Cyaxares

Kurdistan is our religion, our credo,

Let no one say Kurds are dead, they are living

They live and never shall we lower our flag

Thus read the first and fourth verses of Ey Reqîb, the Kurdish national anthem. Like the Assyrians, the Kurds were divided between Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey. Kurdish identity therefore was never established in a state and was instead maintained by emphasizing its continued existence despite being divided up into other states. Kurdish identity, it is alleged, stretches back to Cyaxares, the founder of the Median Empire and conqueror of Nineveh, thereby seeking to legitimize Kurdish national claims in the present by linking them to the distant past.

Kurdish nationalists have never established a state and so have yet to successfully resolve the contradiction between nationalism and statehood. In semi-autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan, non-Kurdish minorities frequently complain of discrimination and attempts to assimilate their identities. Similar concerns have been raised concerning the Kurdish regions of Syria.

What is the response?

The various nationalisms profiled here are vastly different in their aims, resources, coherence, number of adherents, and the degree of moral revulsion they inspire. What they have in common is an emphasis on a particular ancient culture being the special inheritance of an in-group based on primary loyalties rather than citizenship in a nation-state.

One could give many more examples: ancient Israel and revisionist Zionism, Palestinian nationalism (really a stunted version of the second phase), or the way jihadist groups appropriate early Islamic history in the service of claims to re-establish the caliphate. One could further explore the roles played by the ancient past in Hindu nationalism in India or medieval and classical history in the European far right. We can likely expect many more such movements to arise.

Just as the second phase in archaeology was a byproduct of the United Nations-led international system, the third phase is a byproduct of the new nationalisms of the twenty-first century which are bursting through the weak points in the post-1945 international system.

Pre-modern societies provide a powerful model for these new nationalisms, not only because age lends legitimacy but because these societies pre-date the Westphalian state system and therefore lack many of its perceived weaknesses. Furthermore ancient historians have often failed in the past to critically interrogate concepts of ethnicity and identity in the ancient world, especially in the more popular publications, leading to the assumption that these issues were simpler in the past and making it easier to appropriate them for the present.

Possible Responses

Two possible responses to this problem readily present themselves:

The first is internationalism. This is the route taken by the Society for Classical Studies last November, apparently inspired by Donna Zuckerberg’s article “How to Be a Good Classicist Under a Bad Emperor,” which reads in part:

Greek and Roman culture was shared and shaped for their own purposes by people living from India to Britain and from Germany to Ethiopia. Its medieval and modern influence is wider still. Classical Studies today belongs to all of humanity.

For this reason, the Society strongly supports efforts to include all groups among those who study and teach the ancient world, and to encourage understanding of antiquity by all. It vigorously and unequivocally opposes any attempt to distort the diverse realities of the Greek and Roman world by enlisting the Classics in the service of ideologies of exclusion, whether based on race, color, national origin, gender, or any other criterion.

The corollary of this statement is that the second period of archaeology is effectively dead. If the classics belong to all of humanity then they are not the special heritage of any one nation. And if the classics are not the special heritage of certain nations, this calls into question whether national governments have exclusive rights to the cultural heritage contained within their borders. The second period may persist for a while as a legal regime, but its ideology is cut off at the knees.

But internationalism runs the risk of returning to the first period, only with ‘multiculturalism’ and ‘common heritage’ becoming code words for imposing western values and ideas of heritage management on the rest of the world.

The second is localism. Heritage is owned on the sub-national level. Instead of emphasizing the universal value of ancient heritage to the world, localists emphasize the relationships between ancient sites and the communities living in their immediate geographic area. They push for local control over the management of heritage and for hearing their voices in the study of the site.

Aside from the obvious ethical complications (can the locals decide to destroy their heritage? How should they treat the heritage of previous population groups they feel no connection to?) the risk of the local approach is that it can enable the same sorts of particularist nationalism that threaten to destroy the second period system.

Either way, the second period is dead. If the sovereignty enjoyed by the state is undermined, so does its monopoly over the archaeological heritage found within its borders. It is either ceded to international bodies, usurped by ethno-nationalist movements or turned over to local control.

The future of heritage management is going to be complex and likely inconsistent. There have never been simple answers, but the questions are about to get much more complicated.

However, the displacement of the nation-state as the sole actor in heritage preservation provides an opportunity: Not to shift the entire responsibility for heritage protection to another actor, but to introduce balance to the equation. Global, national or local interests will no longer be able to automatically override the other two. Future heritage conservation efforts will likely have to balance the interests of all three.

See Also:

The Future of War in the Middle East and the Future of Archaeology

Archaeology in the Age of Special War

Book Review: “Brave New War” by John Robb

References:

[1] See Zainab Bahrani, “Conjuring Mesopotamia: Imaginative Geography and a World Past,” 159-174 in Archaeology Under Fire: Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East (London: Routledge, 1998).

[2] See for example Magnus T. Bernhardsson, Reclaiming a Plundered Past: Archaeology and Nation-Building in Modern Iraq (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005), 95, 179-185.

[3] Aleksandr Dugin, Putin vs. Putin: Vladimir Putin Viewed from the Right (London: Arktos Media, 2014), 63.

Article © Christopher Jones 2017.

Nimrud Damage Assessment

Following the recapture of the ancient site of Nimrud by the Iraqi Army’s 9th Armored Division on November 13, a steady trickle of news photographers have arrived at the site. As with Palmyra last spring they have come intent on showing the world the state of the ancient ruins demolished by ISIS. Unlike Palmyra, they have also interviewed locals about their relationships with the sites and filed stories focused on the lives of the people in the nearby towns who were persecuted by ISIS.

Although not comprehensive, their photographs and videos allow us to get an idea of the scale of the damage to the site.

Nimrud Citadel

Nimrud’s citadel has been visited by Max Delaney and Safin Hamed from the AFP, Ari Jalal of Reuters, a film crew from the BBC, and photographers from the Iraq Press Agency. Their cameras all tended to be drawn to the same scenes, suggesting these are the most obvious points of damage to the site.

The Throne Room Gate, Northwest Palace

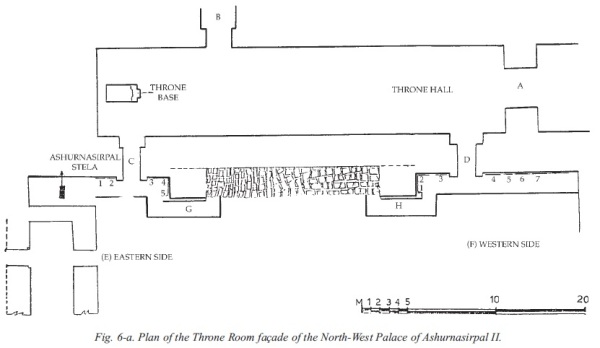

The gateway to the throne room of Ashurnasirpal II’s Northwest Palace was reconstructed by the Iraqi Department of Antiquities in 1956. The project involved reconstructing a section of the walls and several arches. Original sculptures, including two large and four small lamassu and a number of reliefs, were installed at the arches and along the walls of the structure.[1]

Throne room gates shortly after their reconstruction as seen from the outside looking south. From New Light on Nimrud, p. 50.

Plan of the reconstructed throne room. From New Light on Nimrud, p. 50.

Videos posted online by ISIS in April 2015 showed its fighters attacking the reliefs inside this gate with sledgehammers, power tools and earthmoving equipment and piling the pieces of reliefs in a large pile outside the entrance to the palace. This attack took place on or around February 26, 2015 as indicated by many of its perpetrators also appearing in the infamous video of the destruction of the Mosul Museum while wearing the same clothing. Satellite photographs taken for ASOR on March 7, 2015 showed that ISIS destroyed the low wall between the two reconstructed arches in order to provide access for the bulldozer and also showed the pile of relief fragments.

On or around April 2, ISIS returned and blew up the Northwest Palace with several large barrels of ammonium nitrate wired together with detonator cord. The damage was also visible in ASOR’s satellite imagery from April 17, showing heavy damage to most of the structure. The eastern gateway was destroyed, but the western gateway still stood.

Nineteen months later, the large pile of relief fragments remains in place, as does the western gateway, albeit denuded of most of its reliefs and all of its lamassu.

Above: View of the western gateway with the large pile of relief fragments in the foreground.

The Mafia, Looted Antiquities, and the KGB

This week the Italian newspaper La Stampa published a bombshell article in which journalist Domenico Quirico posed as a “rich Torino collector” in order to investigate the trade in looted artifacts smuggled from Libya. Quirico met a man in a butcher shop near Naples who he believed to be connected to the mafia and was shown a bust of a Severan emperor for sale for €60,000 and shown pictures of a much larger statue head being sold for between €1 million and €800,000. Artifacts were said to come from Leptis Magna, Sabratha, and Cyrene and been smuggled through the Italian port of Gioia Tauro. With American art markets under increased scrutiny, they generally go to buyers in Russia, China, Japan and the United Arab Emirates.

More surprising was the claim that this smuggling was part of a triangle of illicit trade, in which artifacts are smuggled from Libya to Italy while the mafia in return buys weapons from black market arms dealers in Moldova and Ukraine and delivers them to ISIS in Libya.

Parts of this story are implausible. ISIS has never controlled any of the archaeological sites mentioned by Quirico’s source (they control only the town of Sirte and made a brief appearance in Sabratha), and most of the sites have been under guard since 2011. The link to ISIS seems unlikely. But could other rebel groups be trading in an artifacts-for-weapons scheme? Possibly, but other aspects of the story give reason to be skeptical.

Quirico goes even further than his contact, claiming that this trade is actually under the control of the Russian intelligence services, who have maintained links with both Chechen and Uzbek Islamists and former Iraqi Baathists now serving in the ranks of ISIS. He further alleges that during the Cold War the KGB traded weapons to the Palestinian Liberation Organization in return for looted artifacts, which were then kept in a secret museum in Moscow before they were gradually given away as gifts to various important figures.

His source for this is “security consultant” Mario Scaramella, a figure who has gained some notoriety as a purveyor of wild accusations regarding the Russian intelligence services. Repeatedly rejected for employment by the Italian intelligence service, Scaramella turned to chasing excitement by hanging around the edges of dangerous games being played by the world’s spy agencies.

The Russian Connection

From left to right: Vassily Mitrokhin, Paolo Guzzanti, Mario Scaramella, Oleg Gordievsky, Alexander Litvinenko. (all pictures from Wikimedia Commons).

Our story begins in Moscow in 1972, when the Soviet KGB began the process of relocating its headquarters from the overcrowded Lubyanka in the center of the city to a new building in the suburbs. The job of moving the massive files of the organization’s foreign intelligence directorate fell to one disgruntled archivist named Vassily Mitrokhin, who had been demoted to a career dead end in the archives a decade and a half earlier and there had grown increasingly disillusioned with the Soviet system. For twelve years until his retirement in 1984 he plotted his revenge on the system by making handwritten copies of the files, smuggling them out in his clothes and stashing them in his dacha in the countryside. There they remained until March 1992, when he boarded a train for Latvia, walked into the British Embassy and turned the entire stash over to Her Majesty’s Secret Service.[1]

The existence of the archive became public knowledge following the publication of the 1999 book The Sword and the Shield, leading many former Soviet turncoats in the West to begin sweating profusely. Among many other things, the book revealed that a major source for Soviet espionage in Italy in the late 1970s and early 1980s was a university professor code-named UCHITEL who was responsible for passing along information about the Tornado fighter jet as well as other military and aerospace projects.[2]

The identity of UCHITEL has never been determined, but in 2002 Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi launched a commission headed by senator Paolo Guzzanti which spent four years attempting to prove that Berlusconi’s predecessor and political rival Romano Prodi was UCHITEL. Prodi had been both a university professor and Minister of Industry during the years UCHITEL was most active. In 1978 Prodi claimed to have learned through a Ouija board where a leftist terrorist organization was holding former prime minister Aldo Moro hostage, a story he is widely believed to have invented in order to protect a source associated with left-wing militants. But other than these entirely circumstantial items the commission failed to find anything linking Prodi to the KGB.

So Guzzanti turned to Mario Scaramella, then a relatively unknown environmental lawyer, to dig up additional dirt on Prodi. Scaramella first pestered Oleg Gordievsky, another former KGB agent who had spied for Britain during the Cold War, for years seeking information tying Prodi to the KGB, information which Gordievsky insisted did not exist.

House Homeland Security Committee Releases Report on ISIS Financing

This week, the United States House of Representatives Homeland Security Committee, chaired by Michael McCall (R-TX) released a report titled Cash to Chaos: Dismantling ISIS’ Financial Infrastructure. The report attempts to give an account of ISIS’ funding structures based on briefings, meetings with federal officials, press reports, and open source document analysis.

Much of the report focuses on ISIS’ major sources of funding from oil, black market commodities, nationalized industry, extortion rackets and kidnapping for ransom. However, the report also discusses the role of antiquities trafficking in ISIS’ funding and makes several recommendations in that regard.

While everyone can agree that countering ISIS’ financing is a key part of defeating the organization, effectively doing so requires accurate information in order to properly allocate resources. Unfortunately, with regards to its treatment of antiquities trafficking this report fails spectacularly in accurately assessing the problem.

For its information about antiquities trafficking, the report relies almost exclusively on reports from major media outlets such as the New York Times, Guardian, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post. Unfortunately major media outlets have frequently been the purveyors of inaccurate information on this topic, and this has negatively impacted the report.

The report correctly identifies Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan as major transshipment points for antiquities smuggling. However, experts on the Syrian antiquities trade generally believe that much looted material either moves east rather than through closely monitored auction houses in London and New York, or that it is kept within the region in hopes of selling it in a few years when suspicions die down.

When it comes to estimating the value of antiquities looting to ISIS the report relies on outdated information, misrepresented statistics, and discredited figures. For example, the report states that:

Before the rise of ISIS, Syria’s antiquities and cultural heritage industry generated more than $6.5 billion annually and accounted for 12 percent of the country’s gross domestic product; thus, even if ISIS captured only a fraction of the market, it could have seen a windfall well into the tens of millions. [p.9]

The $6.5 billion figure comes from remarks made by State Department Assistant Secretary Anne Richard in 2013. It refers not to sales of antiquities but to the entire tourist industry of Syria, and was mentioned by Richard in the context of highlighting the importance of cultural heritage to postwar reconstruction. Since ISIS’ caliphate is a rather unattractive destination for foreign tourists, one can surmise that the fraction of this market captured by ISIS is zero.

Furthermore, the report goes on to say:

In one region in Syria, ISIS reportedly generated $36 million in revenue, partly attributed to its peddling of black-market antiquities. At one point, U.S. officials judged that ISIS was probably reaping over $100 million a year from such illicit trading. [p.9]

The often-repeated $36 million figure comes from Martin Chulov’s reporting in The Guardian. The figure has been widely questioned on this site and elsewhere. Chulov took his figure from captured documents shown to him by an Iraqi intelligence officer. It appears to show income from looting or ghanima, which in ISIS’ terminology means the expropriation of money and property from local populations. Looting of archaeological sites is classified as the extraction of al-rikaz or a “natural resources from the earth” akin to oil, gas, minerals and precious metals. Profits from digging are taxed at a 2o% to 50% rate, unlike ghanima which is expropriated wholesale.

The $100 million figure comes from a February 2015 report in the Wall Street Journal, citing “unnamed U.S. officials.” This is contradicted by figures provided by the US State Department, who estimated in September 2015 that ISIS “has probably earned several million dollars from antiquities sales since mid-2014.”

My own research based on available open source data concurs with this figure, estimating that ISIS has made a few million dollars from antiquities and that taxing looters accounts for less than one percent of the organization’s budget.

Unfortunately, the congressional staffers who wrote this report seem to have simply searched for reports published in major media outlets without critically examining them. Much of the media coverage of archaeological looting in Iraq and Syria has been drive by sensationalism. With reports like this there is a very serious danger that sensationalized articles and bogus figures could drive policy recommendations with regards to prosecuting the war against ISIS.

As it is, the report only makes modest recommendations with regards to policy. It argues that:

Domestic and international law enforcement agencies have not put high-enough priority on tracking black market sales of cultural artifacts and antiquities, which have become a significant source of terrorist revenue. [p. 4]

In response, the report recommends:

The Departments of State, Justice, and Homeland Security should, in coordination with INTERPOL and other relevant international organizations, as well as auction houses, spearhead a new initiative to crack down on illegal trade and trafficking in cultural property and antiquities in the United States and abroad. As part of this effort, various stakeholders should strengthen regulations that restrict the movement of artifacts smuggled out of warzones and take aggressive action to recover and return items to their respective countries of origin. The Committee is supportive of the approach taken in H.R. 2285 (Rep. William Keating [D-MA]), the “Prevent Trafficking in Cultural Property Act,” and urges the Senate to act on this bipartisan House-passed measure as soon as possible.

All of this is fairly common sense material, some of it partially accomplished earlier this year when Barack Obama signed a bill banning the importation or sale of archaeological material from Syria. The Prevent Trafficking in Cultural Property Act is mostly concerned with providing proper training to Customs and Border Protection in cultural property issues.

These are both worthwhile and commonsense efforts. The potential danger lies in if the publicity given to antiquities looting eventually causes a disproportionate amount of resources to be dedicated to stamping out this source of funding, which could better be used against larger sources of revenue. Nearly everyone can agree that the only long-term solution to the threat posed by ISIS is for the group to be defeated as rapidly as possible. We should then all hope for resources to be spent in the most optimal way to bring about this goal.

Article © Christopher Jones 2016.

ISIS Embraces Critical Scholarship of the Bible?

The fifteenth issue of ISIS’ English-language propaganda magazine Dabiq spread across the internet this month. This issue focused on an extended critique of both western secularism and Christianity in attempt to convince westerners to convert to Islam and join the Islamic State.

This blog has previously examined how the increasingly ideological and post-state nature of modern war is creating a situation where scholarship will be increasingly appropriated by armed groups and the purveyors of ideological arguments will frequently become targets. The new issue of Dabiq provides an interesting opportunity to examine an instance of such appropriation in action.

Its centerpiece is a fifteen page article titled “Break the Cross.”Although the article is unsigned, it was obviously written by a native English speaker who appears to be familiar with critical scholarship of the Bible and early Christianity as well as a very basic reading knowledge of Hebrew and Greek.

Upon closer examination, however, the article’s sources appear largely culled from public domain books and other material freely available on the internet. Assuming that the author of this piece is located within territory held by the Islamic State, this may be due to a lack of available resources. Reports that ISIS has burned libraries in the territories it controls could further limit the accessibility of knowledge to the group’s researchers.

The article cites only two very out-of-date scholarly sources by name to support various textual arguments related to the Bible: Strong’s Concordance (published in 1890) and Adam Clarke’s 1831 Commentary on the Bible (making full use of the author’s 19th-century antisemitic prejudices).

The rest of the article’s sources are more obscure but can be revealed through some internet sleuthing. The article discusses – correctly – the semantic relationship between various names for God in Semitic languages (p. 49 in Dabiq issue #15). But then the author gives the name for God in “Chaldean” as 𐎛𐎍 , utilizing a Ugaritic font which happens to be found in the English language Wikipedia page for the Canaanite god El instead of the Akkadian signs for the equivalent noun ilum. (Ugaritic fonts, being alphabetic and therefore containing far fewer signs, are better supported than Akkadian cuneiform fonts on most computers).

The author commits a similar error in discussion of the word בַּר , which means “son” in Aramaic. The author, wishing to argue that Jesus’ contemporaries referring to him as the “bar of God” in their native language could mean something else besides “son of God,” appears to have looked up the Hebrew word בַּר in Gesenius’ 1846 Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon and found that it means “beloved” or “pure” (p. 56). The two are different words, in different languages, and derived from different roots (The Hebrew בַּר is derived from the verb בָּרַר , while the Aramaic has no clear triconsonantal root).

It has often been said that atheists merely believe in one less God than religious people, and many of the arguments the author uses against Christianity can be found on many skeptic websites. Arguments that the Gospels were written at a late date (p. 50), that the date of Christmas was an appropriation of the birthday of the god Sol Invictus, or that the Comma Johanneum is not original to 1 John 5:7-8 (p. 53) are readily found while browsing the online atheist community.

Other arguments are more specific to the online Muslim apologetics community. A number of the Dabiq author’s arguments seem derived from those presented on the website Answering Christianity, maintained by American Muslim apologist Osama Abdallah. Most of what Abdallah writes is standard mainstream Islamic apologetics, albeit in a less polished internet format. Abdallah renounces violence and attempts to spread Islam by peaceful persuasion only, and his website argues that ISIS was created by the CIA and Mossad to discredit Islam.

Nevertheless some of his arguments have now been appropriated by ISIS, including arguments that Simon of Cyrene may have been crucified instead of Jesus as evidenced by Gnostic writings (p. 54-55), that Muhammad was the prophet promised in Deuteronomy 18:18 (p. 59), and the argument that the Greek word parakletos in John 16:7-11, generally taken by Christians to refer to the Holy Spirit, was originally written periklytos, “the admirable one,” and therefore also refers to the coming of Muhammad. (the latter argument was originally made by Muslim convert David Benjamin Keldani in his 1928 book Muhammad in the Bible).

All that this shows is how the work of a great number of people unconnected to and unsupportive of ISIS and their goals has been collated and redirected for the purpose of recruiting people to join the Islamic State.

Thanks to the magic of the internet, everyone is now an expert. And since everyone is now an expert, even a brutal and thuggish organization occupying a stretch of landlocked, mostly undeveloped desert land in the Middle East can now throw together seemingly sophisticated scholarly-sounding recruiting pitches based on amateurish misinterpretations of hundred-plus year old extremely outdated but free and public domain source material.

Welcome to 21st century war.

Deep Maneuver, Robot Warfare, and You

In a previous post, I proposed that people who are seen as purveyors of ideologies which give support to armed conflict are increasingly becoming targets in modern warfare.

Technology allows this to happen. The revolution in artificial intelligence, machine learning and autonomous weapons systems coupled with big-data analysis has the potential to create a digital panopticon which also has the ability to reach out and strike.

This also has the potential to give states an edge against decentralized networks in 21st century warfare.

Robot Warfare

Fielding a fully autonomous robotic army will likely be possible only for a major power. This could make robot warfare the future of war between major powers. Such wars will be limited conflicts fought primarily for interest rather than ideology.

Two scenarios could play out. The first would be a limited struggle over disputed territory such as the Spratly Islands, where each side could feed robot weapons into battle at a steady rate with little risk to any of its own personnel and little chance of serious domestic opposition to the war. Such conflict could go on forever, or at least until the equipment losses for one side or the other became prohibitively expensive.

The second would be a clash between automated armies over some inhabited territory such as the Korean Peninsula or the Baltic states. This is a much more dangerous kind of robot warfare. Once one side’s army is destroyed they now have two options: Surrender, or continue the fight with a human army (likely using lesser quality equipment due to cost, or waging guerrilla tactics).

If they choose to fight on, there will be a strong incentive for the party with an intact robot army to launch a countervalue strike, that is, to attack whatever the enemy values the most. This would serve to minimize their own losses and compel the enemy to quickly surrender.

Possible targets of a countervalue strike could include the civilian population, civilian infrastructure, the food supply, or symbolic, ideological or cultural sites.

Deep Maneuver Warfare

The other possibility involves a tactic called Deep Maneuver. Deep Maneuver refers to the ability of an autonomous system to position itself for an attack weeks, months or years in advance and then activate at just the right moment.

One example of such a weapon is the famous Stuxnet virus. The virus propagated itself through computer systems and removable media, remaining benign until it installed itself on a specific type of computer which controlled the centrifuges used to enrich uranium for Iran’s nuclear program. At this point the virus activated, took control of the system, and spun the centrifuges until they broke down.

Another was the Soviet Fractional Orbital Bombardment System, which was originally designed to put a nuclear warhead in orbit where it could circle the earth with unlimited range and be suddenly de-orbited onto a target with no advance warning. This weapon was judged to be so potentially destabilizing that it was banned from space under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, and finally deactivated from earth under the SALT II agreement.

Deep maneuvering could allow robotic weapons to penetrate all aspects of an enemy country and position themselves for a surprise attack against everything at once.

Such an attack would likely target key infrastructure and economic nodes in order to trigger an economic collapse. Cultural heritage sites of tourist or economic importance could become targets, just as they are for terrorist attacks today.

Cultural heritage sites also form nodes in an ideological economy. Destroying sacred sites causes extensive social disruption and furthermore makes statement proclaiming the superiority of one’s own ideology over that of whatever was destroyed.

Such an attack could take several forms:

- Drones loaded with explosives position themselves days or weeks in advance. At a designated time they swarm cultural and historic sites during peak tourist hours and detonate their payloads. Unlike a suicide bombing or mass shooting, this does not require a commitment to death from those who carry out the plot.

- A virus is programmed which propagates across the internet and erases material which is ideologically opposed to the organization which created the virus. This could include attacking projects seeking to digitally recreate or preserve cultural heritage objects which the group has destroyed. A similar program designed to scrub the internet of ISIS propaganda has been proposed by the Counter-Extremism Project and has received White House backing.

- Micro-drones loaded with small explosive charges identify all the ideological leaders of an opposing group, track them, and then strike all at once. The group is instantly decapitated.

Unlike robot warfare between great powers, all of these scenarios may well be within the capabilities of non-state actors within the next fifty years.

(Photo credit: U.S. Air Force)

Article © Christopher Jones 2016.