Nimrud Damage Assessment

Following the recapture of the ancient site of Nimrud by the Iraqi Army’s 9th Armored Division on November 13, a steady trickle of news photographers have arrived at the site. As with Palmyra last spring they have come intent on showing the world the state of the ancient ruins demolished by ISIS. Unlike Palmyra, they have also interviewed locals about their relationships with the sites and filed stories focused on the lives of the people in the nearby towns who were persecuted by ISIS.

Although not comprehensive, their photographs and videos allow us to get an idea of the scale of the damage to the site.

Nimrud Citadel

Nimrud’s citadel has been visited by Max Delaney and Safin Hamed from the AFP, Ari Jalal of Reuters, a film crew from the BBC, and photographers from the Iraq Press Agency. Their cameras all tended to be drawn to the same scenes, suggesting these are the most obvious points of damage to the site.

The Throne Room Gate, Northwest Palace

The gateway to the throne room of Ashurnasirpal II’s Northwest Palace was reconstructed by the Iraqi Department of Antiquities in 1956. The project involved reconstructing a section of the walls and several arches. Original sculptures, including two large and four small lamassu and a number of reliefs, were installed at the arches and along the walls of the structure.[1]

Throne room gates shortly after their reconstruction as seen from the outside looking south. From New Light on Nimrud, p. 50.

Plan of the reconstructed throne room. From New Light on Nimrud, p. 50.

Videos posted online by ISIS in April 2015 showed its fighters attacking the reliefs inside this gate with sledgehammers, power tools and earthmoving equipment and piling the pieces of reliefs in a large pile outside the entrance to the palace. This attack took place on or around February 26, 2015 as indicated by many of its perpetrators also appearing in the infamous video of the destruction of the Mosul Museum while wearing the same clothing. Satellite photographs taken for ASOR on March 7, 2015 showed that ISIS destroyed the low wall between the two reconstructed arches in order to provide access for the bulldozer and also showed the pile of relief fragments.

On or around April 2, ISIS returned and blew up the Northwest Palace with several large barrels of ammonium nitrate wired together with detonator cord. The damage was also visible in ASOR’s satellite imagery from April 17, showing heavy damage to most of the structure. The eastern gateway was destroyed, but the western gateway still stood.

Nineteen months later, the large pile of relief fragments remains in place, as does the western gateway, albeit denuded of most of its reliefs and all of its lamassu.

Above: View of the western gateway with the large pile of relief fragments in the foreground.

Surprisingly, one relief of a winged genius survives. The breaks on this piece are ancient, they were not caused by ISIS:

It seems that many of the fragments are in large pieces, which means they could hopefully be reconstructed:

Large fragments of a lamassu are visible (source)

Half a relief sculpture survives intact. (source)

The rest of the palace appears to be largely rubble following the massive explosions of April 2015, as this panoramic video by Max Delaney shows:

Although the tombs of the queens of Assyria appeared in ISIS’ official propaganda video showing the destruction of the site, they have not appeared in any of the aftermath images and their status is unknown.

A stone slab with an inscription is visible in one photograph. Ashurnasirpal II’s Standard Inscription repeats itself thousands of times over all the reliefs in the palace:

Several photographs taken by Ari Jalal of Reuters show some rooms near the western gateway whose walls and arches are still standing. However, the reliefs inside these rooms seem to have been smashed.

Picture showing reliefs in a room south of the western gateway shown above. REUTERS/Ari Jalal

Picture showing reliefs in a room south of the western gateway shown above. REUTERS/Ari Jalal

Jalal and Safin Hamed from the AFP took photographs of several other damaged reliefs, most notably several “tree of life” scenes. There were dozens of these scenes carved at the palace, some of which remained there and others of which are housed in museums both in Iraq and around the world.

A damaged “tree of life” scene. Special attention seems to have been paid to damaging the winged genii figures, although it is not clear if some breaks are modern or ancient. (Safin Hamed/AFP).

Fragment of a “tree of life” relief. It is not clear if this damage is modern or ancient. (Safin Hamed/AFP)

The Ziggurat

The ziggurat at Nimrud stood north of the Northwest Palace, across from the temple of Ninurta. The base of the ziggurat was built from large stone blocks and the upper parts were made of mudbrick faced with baked bricks, which by modern times had degraded, leaving the structure looking like a cone-shaped hill.

Unfortunately little excavation work was ever carried out on the ziggurat. A short excavation by the Iraqi Directorate-General of Antiquities under Hazim Abdul-Hamid in 1971 and 1972 uncovered some of the stone walls originally exposed by Sir Austen Henry Layard. Otherwise, no excavations have been conducted there.[2]

Aerial view of Nimrud’s ziggurat. From Oates and Oates, Nimrud: An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed, p. 105.

Based on satellite images obtained by ASOR, ISIS seems to have used heavy earthmoving equipment to level the mound sometime between August 31 and October 2, 2016. A second pass was made sometime before October 16. This event was not publicized by ISIS through any official propaganda channel.

The satellite photographs also show that ISIS destroyed a portion of the temple of Ishtar at around the same time as the destruction of the ziggurat.

October 16, 2016 satellite photo showing destruction of Nimrud’s ziggurat. (source)

The Temple of Nabu

Isometric reconstruction of the Temple of Nabu. From Mallowan, Nimrud and its Remains, vol. 1, p. 232-233.

The Temple of Nabu, situated on the southeastern quadrant of the mound, was partially reconstructed in the late 1970s. The walls were capped with modern baked bricks in order to protect them from the elements. The Fish Gate was reconstructed with its original sculptures in a manner similar to the gateways at the Northwest Palace.

ISIS blew up the Fish Gate last June and publicized the destruction online.

In addition to collapsing the arch, the explosion seems to have dislodged many of the modern bricks, exposing the ancient mudbricks to the elements. Conservation work will be needed in order to save the ancient walls from further damage.

Temple of Nabu looking towards the Fish Gate. (Safin Hamed/AFP)

Nabu’s sanctuary inside the temple of Nabu at Nimrud. (Safin Hamed/AFP)

Mar Behnam Monastery

At around the same time as the recapture of Nimrud, Iraqi troops retook the village of Khidr Ilyas and the nearby Mar Behnam Monastery. The regular army then moved on, leaving the monastery in the hands of the Iraqi Christian militia Kataeb Babylon who gave tours of the site to the press.

ISIS destroyed the tomb of Mar Behnam and Mart Sarah in March 2015. New photos show the dome reduced to rubble but the walls still standing:

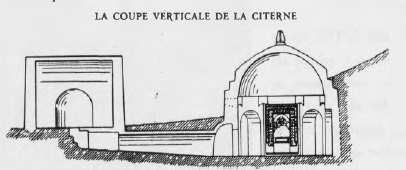

Side plan of the tomb of Mar Behnam and Mart Sarah. From Quelques Vestiges Historiques du Convent de Mar Behnam le Martyr. (Beirut: Syrian Catholic Patriarchate of Antioch, n.d.)

The Tomb of Mar Behnam and Mart Sarah as seen in November 2016. The dome has collapsed from the explosion but the arches are still standing. (source)

Amazingly, photographs indicate that the actual tomb inside the shrine, including one of the few Uighur inscriptions in the Middle East, has survived intact and relatively undamaged.

The grave of Mar Behnam and Mart Sarah. The Uighur inscription is just above the arch. From Quelques Vestiges Historiques du Convent de Mar Behnam le Martyr.

The monastery building was not destroyed. Reports indicate that ISIS burned the monastery’s library and removed crosses. Parts of the building were used as storage or as a prison. Reports indicate that Syriac inscriptions were defaced from inside the complex.

UPDATE 12/10/2016: It appears that the most valuable manuscripts from the monastery’s library were sealed in metal cans and buried in 2014 by the monks prior to fleeing the monastery. They have now been recovered. The collection had been digitized several years ago and is accessible online.

A relief sculpture of Mar Behnam dating from the 13th-15th centuries AD appears to have been completely chipped away, leaving nothing but the outline of where it once remained.[3]

Carving possibly depicting Behnam on horseback, from the church of Mar Behnam. From Quelques Vestiges Historiques du Convent de Mar Behnam le Martyr (Beirut: Syrian Catholic Patriarchate of Antioch, n.d.)

Where the relief of Mar Behnam once stood inside the monastery, November 21, 2016. The graffiti under the damaged relief reads “there is no god but God.” Reuters/Thaier Al-Sudani

A modern relief on the exterior of the monastery depicting the baptism of Mart Sarah by Mar Mattai has also been defaced:

Doubtless many more reliefs inside the monastery have been destroyed which are not seen in the above photographs.

Khorsabad

Despite media reports in March of 2015, the Assyrian royal city of Dur-Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad) seems to have avoided major destruction by ISIS. The site spent two years on the edge of a generally static front line between ISIS and Kurdish forces.

In late October Kurdish forces advanced and occupied the site and the adjacent modern town. Unfortunately Kurdish troops dug military entrenchements on top of walls and palaces which severely damaged the site. Numerous artifacts were uncovered during this operation and were collected by the Kurdish Directorate of Antiquities.

ASOR satellite imagery showing damage to the ancient site of Khorsabad. (source)

Conclusions

The damage to Nimrud is serious and in some cases such as the ziggurat it is likely irreperable. Others such as the Temple of Nabu and the reliefs from the Northwest Palace gateway may be able to be partially restored. The survival of the tomb of Mar Behnam and Mart Sarah is a welcome surprise amidst the destruction.

Reclaiming these sites from ISIS is only the beginning. These sites must be conserved and protected from looters and disturbances in order to prevent further damage, otherwise the loss of cultural heritage may continue even after ISIS is gone.

References:

[1] Rabia al-Qaissi, “Restoration Work at Nimrud,” 49-52 in New Light on Nimrud (London: British Institute for the Study of Iraq, 2008).

[2] Joan and David Oates, Nimrud: An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed (London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 2004), 105-107.

[3] J.M. Fiey, Mar Behnam [Touristic and Archaeological Series 2] (Baghdad: Iraqi Ministry of Information, 1970), 14-15.

Article © Christopher Jone 2016.

It’s the idiot cabal, the controllers with their minions trying to destroy history so that mankind doesn’t find out who they are and what is happening to them now.