What is the Tomb of the Prophet Jonah?

Yesterday the Daily Mail made waves when it reported that ISIS militants in Iraq have smashed the Tomb of the Prophet Jonah (Nebi Yunus in Arabic) in Mosul. A video claiming to show the destruction is included in the article, which shows a black-hooded man taking a sledgehammer to a row of green-painted concrete tombs.

The claim appeared in several places on social media in the past week before the Daily Mail picked it up. However, as detailed at Conflict Antiquities, the scene in the video looks absolutely nothing like the interior of the Tomb of Jonah seen in other pictures. Some sources claimed that the Tomb of Seth was also destroyed, but it doesn’t look like that either. In fact, the pictures were in fact taken in the city of Raqqa in Syria, where ISIS has also destroyed ancient portal lion sculptures.

For now, the Tomb of Jonah appears to be safe. But this might be an opportune time to highlight this intriguing monument and its history.

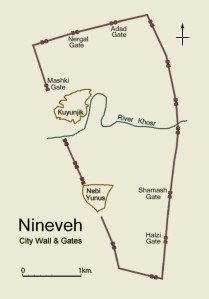

What is now called the Mosque of Jonah is situated on top of a hill in eastern Mosul called Tell Nebi Yunus. The hill is one of two city mounds that form part of the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh. The northern mound, known as Kuyunjuk, is the oldest part of the city dating back to the fourth millennium B.C. The southern mound is Nebi Yunus, and its early history is not known with any certainty. Austen Henry Layard was shown a stamped brick dating to the reign of Ashurnasirpal (884-859 BC) but he was not sure it originally came from Nebi Yunus. George Rawlinson found a stamped brick of Adad-Nirari III (811-783 BC) on the hill but not much else.

What is now called the Mosque of Jonah is situated on top of a hill in eastern Mosul called Tell Nebi Yunus. The hill is one of two city mounds that form part of the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh. The northern mound, known as Kuyunjuk, is the oldest part of the city dating back to the fourth millennium B.C. The southern mound is Nebi Yunus, and its early history is not known with any certainty. Austen Henry Layard was shown a stamped brick dating to the reign of Ashurnasirpal (884-859 BC) but he was not sure it originally came from Nebi Yunus. George Rawlinson found a stamped brick of Adad-Nirari III (811-783 BC) on the hill but not much else.

In 1852, the Ottoman governor of Mosul carried out his own excavations on Nebi Yunus and uncovered a winged bull-man, a statue of Gilgamesh, a statue of a lion, and a lengthy inscription of the Assyrian king Sennacherib (705-681 BC). The governor used chain gangs of prison convicts to do the work. Iraqi Assyrian archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam observed the proceedings and noted “there was no idea of system; therefore the diggings were most irregular, and the tunnels they tried to burrow looked more like the work of those who merely wanted to search for treasure than to uncover an ancient building. The amount of work done by them in one day with four gangs of men I could excavate in a quarter of the time.”[1]

Deficiencies in their excavation methodology notwithstanding, the inscribed slab was the first discovery that began to reveal the history of Nebi Yunus. In the inscription, dated to 690-689 BC, Sennacherib described how a facility called the Rear Palace (ekal kutalli) inside Nineveh was now too small for its purposes and was torn down. “As an addition, I took much fallow land from the meadow (and) I added (it) to it. I abandoned the site of the former palace and filled in a terrace in the fallow land that I had taken from the meadow. I raised its superstructure 200 courses of brick high, measured by my large brick mold.”

A new palace called an ekal masharti was built on top of the artificial hill, and Sennacherib’s inscription went on to describe in detail the construction of the palace. Its roof beams were made from cedars of Lebanon, its doors of copper, cypress and white cedar, and giant bulls made of limestone and pendu-stone guarded the doorways. Below the mound there was a large area for training chariot horses. Much of the cavernous interior was used for storing plunder and tribute from foreign lands, including Media, Elam and Babylon.[2]

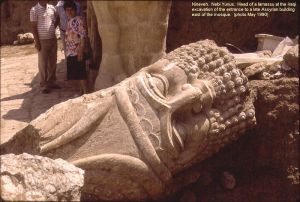

In 1954, some construction work created a window for a limited excavation by Muhammad Ali Mustafa and the Iraqi Department of Antiquities, which uncovered an ancient retaining wall with a cylinder inscription of Esarhaddon inside. They also uncovered a massive 35 meter wide gatehouse. At the bottom of the tell they found watering troughs labeled “belonging to the palace of Sennacherib.” Further work was carried out from 1988 to 1990 by David Stronach from the University of California at Berkeley before the Gulf War cut off American access to Iraqi sites. The results have not yet been published, but available photographs show a number of giant bull colossi and sculptures.[3] They confirm the inscriptions describing a major structure built on the site.

The palace was renovated and expanded by Esarhaddon (681-669 BC), and renovated again by Ashurbanipal (669-627). It was destroyed during the Sack of Nineveh in 612 BC. But extensive excavation has always been impossible, because sometime in the early Christian period a church was built on top of the tell. At the end of the seventh century AD the Christian Patriarch Henanisho I took up residence there after being deposed from his post, imprisoned, and thrown off a cliff by his captors. Crippled for life, he would be buried at the site upon his death in AD 701. The church was renovated by the Patriarch Sargis in the late ninth century. At some point, and it is not at all clear when, the tradition seems to have developed that the tell and the church on top of it marked the grave of the Biblical prophet Jonah.[4]

In the Biblical Book of Jonah the prophet was sent to prophesy not to Israelites but to the people of Nineveh, and as a result Jonah has always been especially venerated in the Assyrian Church of the East. The church became a holy place for Assyrian Christians.

But one of the great archaeological quirks of sacred space is that it always stays sacred. The Temple Mount in Jerusalem is the most obvious example: throughout its history it has hosted a long sequence of Jewish temples, pagan temples, churches and mosques. Sacred space stays sacred in two ways: Sometimes the practitioners of a new religion feel compelled to recognize a place as sacred, and develop their own reasons to continue to venerate it. Other times, they choose to demonstrate the superiority of their own religion over other belief systems by destroying their sacred spaces and building their own in their place.

It was clearly the former process at work on Nebi Yunus. Jonah is recognized as a prophet in Islam. Sura 10 of the Qur’an is named after Jonah and contains numerous allusions to the Biblical story comparing Jonah’s mission to the Ninevites to Muhammad’s prophetic career:

He it is who enableth you to travel by land and sea, so that ye go on board of ships – which sail on with them, with favoring breeze in which they rejoice. But if a tempestuous gale overtake them, and the billow come upon them from every side, and they think they are encompassed therewith, they call on God, professing sincere religion:–“wouldst Thou but rescue us from this, then we will indeed be of the faithful.” But when We have rescued them, lo! They commit unrighteous excesses on the earth!” (Sura 10:23-24a).

Verily they against whom the decree of thy Lord is pronounced, shall not believe, even though every kind of sign come unto them, til they behold the dolorous torment! Were it otherwise, any city, had it believe, might have found its safety in its faith. But it was so, only with the people of Jonah. When they believed, We delivered them from the penalty of shame in this world, and provided for them for a time. (Sura 10:96-98).[5]

Thus began the strange afterlife of John the Lame, of whom the early 1900s British traveler Edgar Wigram wrote “now gets compensation for a life of hardship in his posthumous honors as Jewish Prophet and Mussulman Saint.”[6] The shrine at Nebi Yunus was rebuilt as a mosque during the reign of Tamurlane, at around 1393. In 1849, Austen Henry Layard was able to visit the shrine several times, which he described as “a square plaster or wood sarcophagus, entirely concealed by a green cloth embroidered with sentences from the Koran.”[7]

“No more genuine, alas, than the body of Jonah are the remains of his whale, which are suspended over the tomb,” wrote 1920s British traveler Sir Harry Charles Luke. “These consist of three sections of the ‘sword’ (if that be the correct term) of a swordfish, posing here as the backbone of the squeamish monster.”[8]

Over the years, the remains of the whale dwindled to a single tooth, and then even that relic disappeared. In 2008, the U.S. Army presented the Imam with a museum quality replica of a sperm whale tooth to take its place.

Layard and many others expressed their desire to bulldoze the shrine so they could excavate the palace underneath. Since they understood the shrine did not actually hold Jonah’s body, they saw no problem with tearing it down to get at the more interesting stuff underneath except that it might upset the locals. Their feelings weren’t important either, it’s just that their nasty habit of rioting when foreigners dug up their graves and sacred places might stop the work.[9]

Giv’at Yonah in Ashdod, Israel. Identified in the Madaba map as the tomb of Jonah, it is the site of a modern lighthouse.

Layard, Luke and others were correct on one account: this is not, for sure, the actual tomb of Jonah. While the existence of a historical religious figure from Gath-Hepher named Joseph son of Amittai seems to be supported by 2 Kings 14:25, details about his life and final resting place are completely unknown. This has not stopped a half-dozen places from claiming to be the site of his tomb. In the fourth century Jerome wrote in his Commentary on Jonah that Jonah’s tomb was displayed in a small village near Sepphoris, and indeed the ancient site of Gath-Hepher sits outside the Israel Arab town of Mashhad, which to this day claims to have Jonah’s tomb.[10] North of Hebron in the West Bank sits Mount Nebi Yunus, the highest point in the West Bank and home to another tomb of Jonah. There is yet another tomb of Jonah at Jieh on the coast of Lebanon, and another near Apamea in Syria. Yet another story holds that Jonah was buried on the hill named Giv’at Yonah on the north side of Ashdod in Israel, a spot currently occupied by a lighthouse.

It goes without saying that even though it is almost certain that none of these places are the actual tomb of Jonah, they are still valued by the local populace and destroying any one of them would be an offense against their cultural heritage and local history.

But furthermore, these shrines show that cultural heritage is not something static, a series of ruins of the past awaiting someone to dig it up and discover it. Rather, culture is part of a discourse between past and present. These shrines are not simply obstacles to historical research or products of historical ignorance, but an expression of the connection felt between the present inhabitants of the region and their past.

On one level, it does not matter if any of these tombs contain the actual bones of Jonah son of Amittai. I doubt that anyone goes to the tomb of Jonah in Mosul to contemplate the international politics of the eighth century B.C. or the evolution of Israelite views of Assyria. They do visit these shrines to meditate on the questions raised by the story of Jonah: questions of justice, obedience, providence, fairness and divine mercy.

And that’s cultural heritage.

Update 7/24: Sadly, the Tomb of Jonah was blown up by ISIS on July 24, 2014.

For more views of the shrine at Nebi Yunus and the ruins of Nineveh, check out this tour posted on YouTube (commentary in Arabic):

References:

[1] Hormuzd Rassam, Asshur and the Land of Nimrod (Cincinatti: Curts & Jennings, 1897), 4-7; Geoffrey Turner, “Tell Nebi Yunūs: The Ekal Māšarti of Nineveh,” Iraq Vol. 32, No. 1, (Spring 1970): 68-72.

[2] Lines 55-90 ofSennacherib #34 in A. Kirk Grayson and Jamie Novotny, The Royal Inscriptions of Sennacherib, King of Assyria (704-681 BC), Part 1 (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 2012), 219-226. Also available online at http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/rinap/rinap3

[3] Naji al-Asil, “Editorial Notes: The Assyrian Palace at Nebi Unis,” Sumer, Vol. 10 (1954), 110-111; M. Louise Scott and John Maginnis, “Notes on Nineveh,” Iraq, Vol. 52 (1990), 64-67.

[4] Joel Walker, “Nineveh,” in Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage (Gorgias Press, 2011), 309-310; E. Wallis Budge, The Book of Governors: The Historia Monastica of Thomas Bishop of Marga, Vol. 1 (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Tubner & Co., 1893), cii-ciii; Harry C. Luke, Mosul and its Minorities (London: Martin Hopkinson & Co., 1925), 34.

[5] The translation I use here was made by J.M Rodwell.

[6] Edgar T.A. Wigram, The Cradle of Mankind: Life in Eastern Kurdistan (London: A & C Black Ltd., 1922), 85.

[7] Austen Henry Layard, Discoveries in Nineveh and Babylon (London: John Murray, 1853), 596.

[8] Luke, Mosul and its Minorities, 34-35.

[9] Layard, Discoveries in Nineveh and Babylon, 596-598; Wigram, The Cradle of Mankind, 84-85.

[10] Jerome’s commentary on Jonah can be read here: http://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/115/

Image Sources: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Nineveh_map_city_walls_%26_gates.JPG; United States Department of Defense Cultural Heritage Action Group (http://cchag.org/html/09476/iraq05-050.html); http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nineveh_Nebi_Yunus_Excavation_Bull-Man_Head.JPG; United States Library of Congress (http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/mpc2010000417/PP/); United States Army (http://www.dvidshub.net/image/133831/tomb-jonah-complete-again#.U8AwkLGtwYY); United States Army (http://www.dvidshub.net/image/133822/tomb-jonah-complete-again#.U8Awm7GtwYY); photo of Giv’at Yonah © Christopher Jones 2012.

Article © Christopher Jones 2014.

Trackbacks

- the Tomb of Jonah may have been destroyed, but it was not in this video: a retraction and correction are in order | conflict antiquities

- Muslim extremists, ISIS claim they have destroyed Jonah’s tomb in Ninevah - The Global Dispatch

- video of “destruction of Tomb of Prophet Jonah” is from at least ten months ago | conflict antiquities

- Video: Islamic Terrorists Blow Up Tomb Of Jonah The Prophet In Iraq | Health Treatment

- Why Did ISIS Destroy the Tomb of Jonah? | الحرب الطائفية في المملكة

- Why Did ISIS Destroy the Tomb of Jonah | Fr Stephen Smuts

- On the destruction of the Tomb of Jonah | Things that lurk in the dark

- You had me at ‘pretty much anything’ | conflict antiquities

- ISIS Destroys Traditional Tomb of Prophet Jonah | Sign of Jonah

- ISIS Destroys Traditional Tomb of Prophet Jonah | Prophet Mohammed (Muhammad) Was Nehemiah of Israel

- La cultura universal, víctima del extremismo | Las verdades de un Tal

- Jonah’s Nineveh and Modern-Day Mosul | Veracity

- Biblical king’s palace found – Trending News

- Biblical king’s palace found – G Email News

- Biblical king’s palace found | Our Ladies and Gentlemen

- Biblical king’s palace found |

- Biblical king's palace uncovered beneath shrine destroyed by ISIS | Breaking News

- Biblical king’s palace found | shaheenMediaSialkot

- Biblical king’s palace uncovered beneath shrine destroyed by ISIS | Our Worlds Mysteries

- Biblical king’s palace uncovered beneath shrine destroyed by ISIS | Cthis.info

- Biblical king’s palace uncovered beneath shrine destroyed by ISIS | Michael Bradley - Time Traveler

- Recientes hallazgos arqueológicos en Asiria corroboran las Escrituras - Mi Devocional

I’m wondering why Jonah would be buried in Nineveh or why he would want to be buried there. He despised the city and reprimanded God for not destroying it. The Old Testament doesn’t say he was executed or that he died there, and he came from the Northern Kingdom of Israel. It puzzles me why this would be his accepted tomb, based upon what the Old and New Testaments say.